Even after years of studying how the public sector machinery churns, there are still aspects of it that astound me – where I want to rub my eyes and say: how…? why…? One of those aspects has to do with language and something of an “emperor’s new clothes” problem. Only not quite, because there are many people pointing at it and calling it out: New Zealand’s propensity to fill its central policies and strategies with vapid, pompous, meaningless language.

Sound and fury

One of the best ways I first heard this addressed was in a conference presentation by Sarah Bickerton – talking about “space policy”. What an exciting pitch, isn’t it? Anything with space in it…

Bickerton’s contention was (and I’m paraphrasing here) that the policy was dominated by generic language and corporate speak that offered very little concrete that one would expect from such a crucial document. While there are big descriptions of the significance of the policy, the role of the space industry for New Zealand, and lofty illustrations of what the future might hold – it says next to nothing about what the government will actually do. Their study et al (sorry, not open source) gives some great examples:

“While the documents call for accelerated sector growth, they do not address the source of the investment to set up and sustain this business development, or whether the Government will assist through grants, loans, tax schemes, employment regulations, etc. For instance, space-related technological development in other countries is often co-financed by the government, which helps steer the industry towards the nation’s space goals.

It is also unclear in the strategy document if the Government’s goal is to maximise local workforce recruitment or whether talent is to be recruited internationally. Both options require Government support through, for example, employment or visa schemes, targeted education, investment and vocational pathways.”

I had a look at the updated strategy from 2024, which does a little better as it lists actions such as: “Establish a national mission through the development, manufacture, launch and operation of one or more sovereign satellites” (I hope it wasn’t that one), and “Establish the Prime Minister’s Space Prizes to inspire the next generation of aerospace professionals.”

But you also still find plenty of my favourite empty action-words: deliver, enable, empower, or: “ensure government is well positioned to use aerospace-enabled data”, and “work closely with our international partners to promote cooperation”.

Ok. How do you ensure that? What avenues and leverage do we have?

It also ticks another one of my favourite strategy-boxes – declaring New Zealand’s intent to be “world-leading” at something massive:

“Establish a world-leading regulatory environment for space and advanced aviation”

Pardon my cynicism here, but we really seem to only have two speeds: tall poppy or world-leading. We don’t do anything in between…

Yes, you can read that as an expression of ambition, harmless hybris. But to me it’s a big red flag pointing at a fundamental issue. Because I don’t believe we need government strategy to be ambitious beyond the achievable – we need it to demonstrate that our administration has a clear and realistic understanding of the field it’s addressing. And when the language of such documents drifts heavily into the positivistic, I forget that I read government policy and could be convinced I’ve accidentally opened the corporate report of a major bank.

Different strategy, same cookie cutters

I know a little more about AI than I do about space – but seemingly that doesn’t matter much because the nature of the language is all too familiar. As the government’s AI strategy was introduced last month, it rained criticism left, right and centre. For example by Chris McGavin:

“To be blunt, the document is poorly written, badly structured, and under-researched. It cites eight documents in total, half of which are produced by industry – an amount of research suitable for a first year university student. It makes no effort to integrate arguments or sources critical of AI, nor does it provide any balanced assessment.”

On the surface, the document does better at pointing to actions than the space strategy did. In fact, it lists so many of them that one could get the impression that a lot is being done. But when you stop and think for a second, you find there’s no filling in the compliment-sandwich.

The strategy posits a list of barriers that exists in NZ to the adoption of AI. First off: “Regulatory uncertainty. Some businesses perceive uncertainty about how existing laws apply to AI applications and what additional compliance requirements may emerge.”

The “Action: Commitment to stable and enabling policy” in response is phrased as:

New Zealand is taking a light-touch and principles-based approach to AI policy. New Zealand has existing regulatory frameworks (e.g., privacy, consumer protection, human rights) which are largely principles-based and technology-neutral. These frameworks can be updated as and when needed to enable AI innovation, and to address new risks and unintended interactions with legislation. This agile approach gives clarity to businesses whilst ensuring New Zealand can respond to new technological developments.”

Does everybody see what happens here? Let’s break that down:

A statement of intent = this government’s intention is to be “light-touch” on AI policy. That’s your position - good

We have regulation.

That will be updated to “enable” AI innovation

“as and when needed”

“that gives clarity to businesses”.

No, it does not!

Yes, there is some hint of a declaration of intent, but followed by what I can only describe as an exemplary commitment to uncertainty. Literally the opposite of that is claimed. Will there be updated regulation, where, how, when? Sound and fury.

Across the board, the listed actions follow a similar pattern or are “continue to” statements – referring to processes that are already ongoing and merely signal some form of general consent with no ownership, and – again – no articulation of what that actually means, what can be expected from it, and what the actual concrete plans of the administration are, other than “enable, empower, deliver”.

That’s not strategy, that’s turtles all the way down.

We can’t seem to get away from these broad declarations of intent as substantial parts in the documents that need to act as cornerstones of the two extreme ends of active government intervention – investment and regulation.

And of course, let’s tick that box:

“New Zealand has a growing AI ecosystem, with many organisations already delivering innovative and world leading solutions.”

Sure, fine.

The yada-yada-yada approach

This semantic hand-waving is so familiar to me through my restructure analysis. I’m categorising 60% of the 494 restructures that happened between 2018 and 2021 as having a “strategic-aspirational” reasoning. As in, the language used to explain why a restructure was needed and the goals that it means to fulfill are presented in broad, ambiguous, generic language.

A key characteristic of this type of narrative is that you can’t reasonably disagree with it.

It’s like saying: we all want to be happy and healthy. Sure, that’s pretty universally true – but what that means for the individual differs wildly.

And that’s where policy and strategy SHOULD be living. That’s where the articulation of intent, reasoning and actions matters!

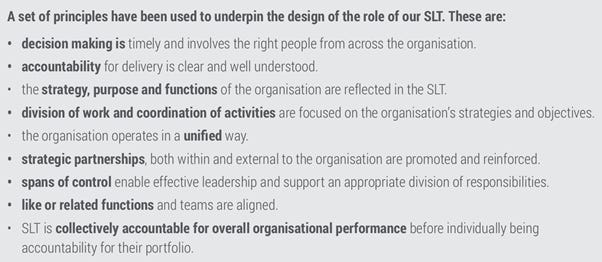

What you tend to find in restructuring is language like this, describing the design principles of FENZ’ new governance model in 2018:

Again - if you can’t reasonably disagree with such statements - what is their value?

Is it bad to put things in writing to be 100% clear? no. Are these different from ANY other leadership principles? no. Does this explain anything about the actual structural choice that are being made - supposedly based on them? not. one. bit.

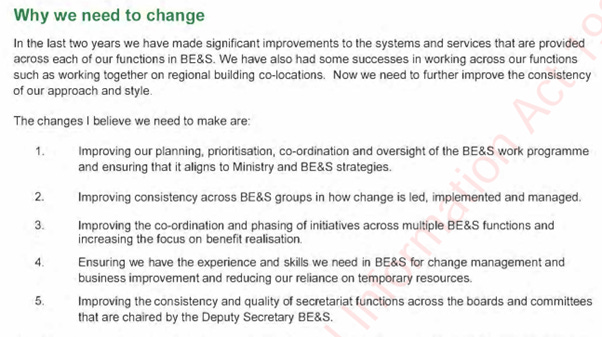

Or take this example from the Ministry of Education’s “Business Enablement & Support” function:

And honestly, I’ve opened two documents in my database at random to find these examples. That’s how common this language is.

As with every restructure – the people who were there can probably tell another story of how everything came to be. But staying on the question of language – what does this text actually say? Hot air.

The repeating pattern I see is this:

Somewhat reasonable and detailed description of the status quo & a historical retelling of how we got there.

High-level problem description: silos, clarity, efficiency, fit-for-purpose, etc.

Boilerplate vision statement: world-class function, efficient, timely, trusted, etc.

Yada Yada Yada

Here’s your new structure & impact table on your roles.

The real crucial part of the whole plan is what goes on in the black box - that is what makes or breaks it. Yet, the highest-paid, most influential people who are charged with settings the pathways for us seem to shirk responsibility and hide behind shiny words.

Sure, when you try and simply address a complex issue, it makes sense to start with big-ticket statements. But you need to work your way down from there, from the generic to the specific. And that’s what so many of these documents seem to obfuscate. I’ve described this as a black-box problem in organisational change, not coincidentally, also a term commonly used to describe the lack of transparency of the decision-making in AI.

Why might that be?

World-class bullshitting?

As I see it, there are three scenarios that might explain why we see these patterns in how strategies, policies and plans are shaped and communicated:

Political sleight of hand

The examples I used, AI, space stuff - that’s all pretty hot and still developing. So perhaps the fact is that either the government of the day, or the public leadership, just don’t really know all that much about a topic yet, or don’t yet have a clearly actionable agenda. That may particularly be true in the year or so after a change of government – which in New Zealand’s case can be true for quite a few years in any one decade.

But if there’s public pressure there may be a need to say something, rather than nothing. And so something is pulled together as good as it can be for the moment. If you look at the space policy – I would say there is an improvement in clarity between the policy in 2023 and the updated strategy a year on. And that’s good and fair.

But if that was the case… what’s wrong with saying so? At no point in these documents is there clear acknowledgement that this is a developing area and that the current high-level thoughts need to be made more concrete later.

In the first months of Covid, I recall this being a frequent response to big and complex questions: “we don’t know yet, but we’ll tell you once we have figured it out.” Whatever else you might think of New Zealand’s Covid response – in my eyes, this kind of honest communication made the people at the helm more credible.

I think this comes from a tricky cultural setting, where especially leader in certain spheres assume that in order for something to have credibility, it has to be presented with utter, unshaken confidence – or else you seem weak or open yourself up to criticism. But the thing is,

we all know “corporate speak“ when we hear it. There’s a degree to which you can polish up a bad news-story and present it in a better light. But you cannot convince people that your empty hand-waving is something of substance, when it is not.

This kind of speak is there to distract us in a best-case scenario, or to pull the wool over our eyes in a worst case. And the latter can dangerously undermine people’s relationship to their government. If you wonder why some people don’t feel represented by their government, no matter what coalition is in charge - look at the language they use. Who is impressed by that?

Intentional ambiguity

There must be people out there to whom this kind of writing is “best practice”. Where in fact, everything that I’m shaking my fist at here is intentional – it’s not supposed to be clear, concise and applicable.

It’s supposed to be a performative artifact that wedges open a semantic door through which many-an action might be shuttled that you wouldn’t want to cleanly articulate in writing.

This is the Machiavellian interpretation of things, using general and ambiguous language to your benefit. West-Germany’s first Chancellor Konrad Adenauer is supposed to have said “What do I care about yesterday’s tattle”. You can’t be held responsible, if you never clearly nailed anything down. Smart.

Collective delusion

By that I mean a state that a group of specialists and leader might have gotten themselves into while developing such a strategy, policy of plan. Perhaps this is what happens when a smart and motivated group of people tries to write an AI strategy: it goes through so many rounds of negotiations, and so many arguments around the semantics of it all, that you slowly but surely become satisfied with just anything that the stakeholders can agree on. And

Perhaps when we work in such settings, group think and path dependence, plus our weaning patience, drive us to continuously push what we’re saying further and further up into the abstract, the generic – because as I said before – when you reach that level, you can’t possible disagree anymore.

In this option, you don’t need Machiavellian intent, just the fallibility of humans in group dynamics. I recall many-a lengthy workshop with seniors and executives where I had these third-eye moments, watching highly-experienced people around me debating with great seriousness whether something should be called an action, a task, or an initiative. For hours.

I’m not saying that these details don’t matter – words matter. But I wonder if the process by which we committee such documents into being may sometimes drain the life out of them. Whenever I was part of such a process, they sure did that to me. And so, un-moored from all accountability and practical delivery - our policies, strategies and plans float in space.

You're like an arrow into a bulls eye. It feels goods to vent. To hear someone say/write what you are thinking feels good.... but will it change anything?

It's not just government departments that are full of "sh1t" it is in my view most large NZ companies and they keep employing (or contracting out) huge amounts of BS "communications" because the only plans or strategies they have is to keep going as they are, heads down, make a profit, ignore the environment, to hell with the grandchildren.

A government that changes every three years and even if they don't change they have no plan for 3 or more years. I cry with frustration and I'm angry with them for my grandchildren. And finally I'm frustrated that the very good points you make are not able to be translated into some actions or communications with those "floating voters" that might make a difference at election time.