Co-Design – a cautionary tale

What’s missing from our conversation about an essential skill for public service

There's a German phrase that I often use in its roughly translated form because I find it so fitting:

“Dangerous half-knowledge”

It describes situations in which people are confident they know what they're doing, but they actually don't know enough to understand the limitations that can get them into trouble. Sometimes it's better to know that you know nothing and approach a situation openly and carefully.

There is a lot of “dangerous half-knowledge” when it comes to co-design and co-production.

Let's get this on record straight-up: I think it’s more than pressing that we get a solid handle on what co-design means in public management. It may sounds like a millennial buzzword from the well of “agile, MVP and citizen-centric”, but it describes the fundamental ability of institutions like public service to directly and actively involve people in the process of how public services are thought of and provided.

Being a buzzword, nevertheless, “co-design” is being used to excess in strategies, visions and other forms of high-level, generic manager-talk - which risks draining it off its meaning and causing people to roll their eyes at its mention before it ever had the chance to be road-tested in decent conditions.

I found that the term splits public servants into two camps: those who roll their eyes at its mere mention, and those who use it whenever they mean engaging with the public in some share of form. And there’s your problem, right there. They're often in that dreaded state: dangerous half-knowledge.

It’s not their fault – I do believe that much of what has been called “design” in public service has sold a rose-tinted version of what actually happens in practice.

More than anything, co-design requires a reflection of power, discretion and limitations.

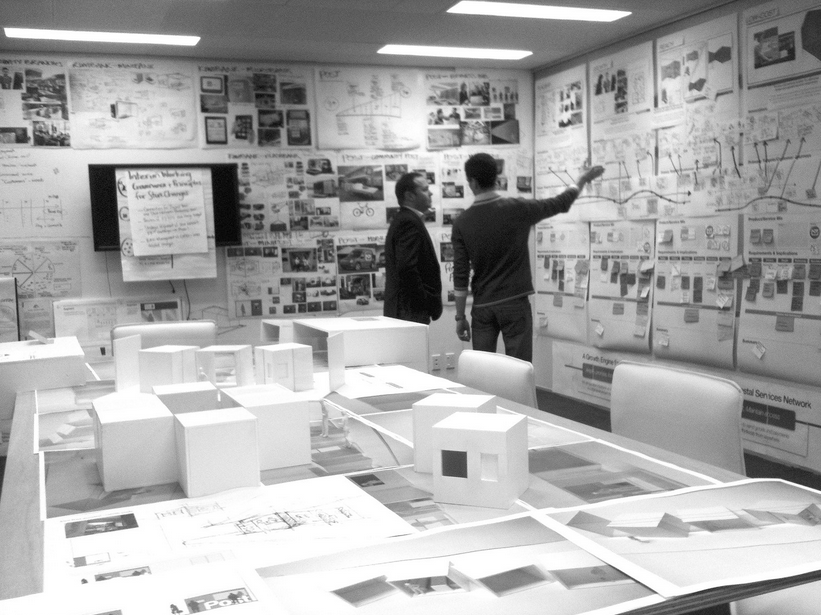

A good context for co-design means that there is actual space to design, as in, to create something. A clear enough brief of what there is to do and open enough that anyone can get amongst it and see their ideas add to the bigger picture. Like the retail transformation that NZ Post and Kiwibank ran over many years, trying to make better use of their shared locations. For a while the programme team had a large space out in Petone where it could run physical prototypes: they taped the floor map of a retail space on the ground and marked out a few set fixtures, and then the customers and designers could freely try out different constellations of how the space could be used. They moved around cardboard furniture and tested ideas with people trying to queue in the space, until a workable configuration came together.

The solution had to be within a certain budget but the other limitations where, literally, in your face. The space had to work for different people, it couldn’t be made bigger, you couldn’t move structural pillars. So it put everyone – the experts, designers, and customers into the same sphere where they could genuinely co-design an idea.

But boy howdy – that’s a rare case.

In most public service contexts, limitations and conditions within which a solution might to a problem be found tend to involve policies, budgets, stakeholders, procurement processes, interdependent systems, regulatory cycles and so forth. So you can set a “design challenge” and invite citizens to comment on how they would like a service to work – but you tend to end up with a whole bunch of ideas that are simply impossible.

What follows is a meeting room with business analysts, advisors and managers making judgement calls as to what is possible within all the limitations that might still work for the citizens. And that’s where the distortion sets in – no matter how well intended. What comes out in the end tends to be unrecognisable from the ideas that the people shared.

I’ve been through this so many times, alas, every example I can think of is too sensitive for me to name.

Potato-potato - why is that a problem?

People have started to refer to “co-design” for a reason. The ambition is to signal a public service practice that takes the citizen-perspective serious, that is less elitist and “designs services around the needs of the citizens”. And that’s fine as an ambition.

The trouble is when we just start using this term for everything that even remotely involves a member of the public, because is insiuates a level of participation that doesn’t exist.

There’s a difference if you gauge people’s needs and opinions and negotiate and construct a solution “with the citizen in mind” - but still as an expert from a position of influence - OR if you create a situation in which the citizen is actively involved in that negotiation, outfitted with the knowlede necessary to make judgement calls, and to have influence of their own!

We should call something “co-design” when there’s a situation in which the public specialists and members of the public can get themselves on a level playing field: each with different perspectives and interests, but all starting with some level of understanding of where the costs, pay-offs and limitations are.

That’s not to say that we have to educate all customers to become experts before they can co-design. It’s much more about knowing what situation CAN be co-designed, and what does require an expert hand. More often than not, best you can do is research and test with users - that’s grand.

“Dangerous half-knowledge” around co-design means that we increasingly drain the meaning from this important term, growing the number of eye-rolling people – because they’ve heard it all before and “it doesn’t work”. But that’s a topic for another day.