After last week’s post in which I wrote about the sometimes paradoxical role of external consultancies in the public service, I fell into a bit of an rabbit hole that took me all the way across the pond to our cousins. It started with something a fellow public management researcher from Australia pointed me to: the fact that the Australian Public Service (APS) has established an in-house consulting unit:

“to provide professional services to agencies, reducing the reliance on external consultants, while contractors will be used ‘only when suitable and required’.” Source

That’s quite something, isn’t it?

To me, it’s one of those thought-grenades that goes off in your head and stays with you. With all the benefits that we – rightly or wrongly – associate with the role of consultants in mind, it makes perfect sense: get an outside perspective on a wicked problem, get professional advice that’s difficult to procure, a capability you might not need at all times in your organisation. But instead of hiring a gang of over-worked recent graduates and 0.2 of a director on billable time from one of the “big four” – you get the same service from actual public servants, employees under the same (supposed) moral code and long-term outlook as you.

My instant reaction was: what could be more sensible? Why don’t we do that?!

But let’s have a closer look across the Tasman first:

The inception of this unit was one of the consequences of the Australian Senate’s inquiry into the capability of the APS from 2021. The inquiry had cited public administration researchers who spoke of a “para public service” and listed a hefty stack of concerns around free and frank advice, transparency, the interest of consultancy firms, and perhaps most remarkably, that:

“(…) the ongoing, unnecessary use of consultants by governments has gradually eroded the APS's strategic policy capability.” Source

If you read the whole inquiry report, you’ll see the criticism goes a whole lot further than what I described in my post last week.

The in-house consultancy was then founded in late 2023, placed inside the Department of Prime Minister & Cabinet with $10.9 million funding for two years, and was part of a wider strategy to reduce spending on “external services” by 3 billion – though I’m not clear on what proportion of that chunky savings target was expected to be the result of their services.

A former McKinsey and Bain consultant who has also been a public servant for years was recruited to lead the unit, which was said to “deliver at least 15 projects” over two years, and its first publicly named projects sound hella consultancy-speak to me:

“Partnering with the Centre for Australia-India Relations to analyse opportunities for closer collaboration between federal and the state and territory governments on economic engagement with India.

Partnering with the new Net Zero Economy agency to develop its vision and undertake strategic business planning.” Source

In the host of press releases filled with generic benefits/opportunities/vision speak, I spotted an interesting expectation of the unit’s role:

“Clients will have the opportunity to practise and implement in-house consulting methodologies through a collaborative approach to project delivery. Over time, the tested approaches to capability uplift can be rolled out across the APS.” Source

So far so sensible.

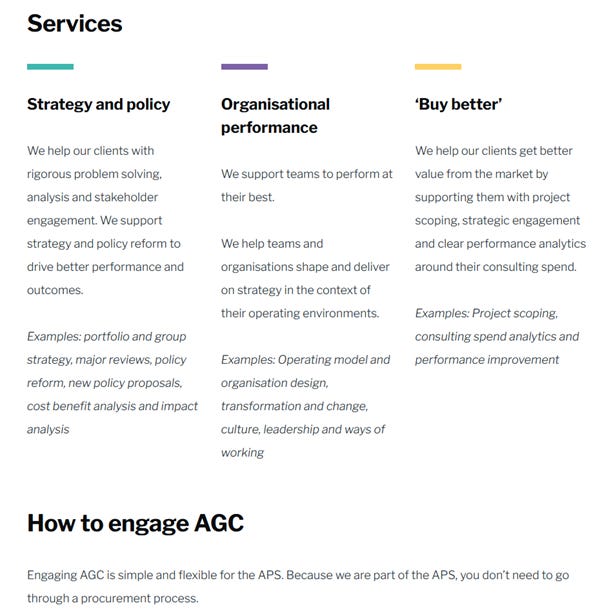

I got a big kick out of the unit’s own website. It’s the simplest, most under-stated public service representation I’ve ever seen, and I can’t help but celebrate it: It has 4 extremely brief section: about us, services, our people, and contact. I’d be surprised if it’s more than 400 words across the lot, and here is all they say about their services:

Strategy, org performance, procurement – BAM! And my favourite: “you don’t need to go through a procurement process” – that’s a public service mic drop.

As someone who has read more than a thousand generic, business-blahblah, vapid strategy language documents, this approach to representing what they do is a genuine breath of fresh air to me! But that may be my personal bugbear.

They’re probably wise not to invest heavily into a web presence – I doubt that any APS worker will be able to contact them and call them in like the public service cavalry.

They say they have “more than thirty people drawn from across the APS, state public service and private sector” (source) – so with 15 projects over 2 years I bet they’re more than busy.

The consultancy has been called a “pilot” in a few sources I’ve read, so it only makes sense to start with something manageable and have the chance to work out a lot of the wrinkles that inevitably show up when you try a different approach.

This all sounds brilliant – where’s the catch?

Soon after the inception of the consultancy was announced, there was gesturing towards the example of the UK which had “shut down” its in-house consultancy model, and “quietly removed spending caps for departments on consultants” (source).

It’s only sensible that we look at other jurisdictions to see if we can learn from them, or from their mistakes if you will. Heck, that’s what I’m doing right now, eh? But if we look at what others do and take the adoption or abandonment of a certain glitzy programme as direct evidence of failure or success - we’d be naïve, to put it mildly.

The question is - why did the UK example get pulled?

The article that describes this reference to the UK in-house consulting being shut down mentions:

“The public service minister added she understood the UK model to be a cost-recovery model which “affected the buy-in”.”

And then cites an APS DepSec saying about the UK case:

“[They] let me know that the model was well regarded, but the funding for the function was reprioritised to other priorities.”

To me, these are excellent examples of where the focus of such crucial and potentially far-reaching pilots should be: on its setup, and its political landscape.

The question whether an in-house consultancy should be cost-recoverable or not was actually the first one that came to my mind when I heard about it. I’ve seen this before when I was working in internal “centres of excellence” (yes… they called it that) at larger institutions.

On the one hand, the internal specialists (all design-y folks) often complained about being called onto projects nilly-willy -

as decorative but ineffective tick-box seats around a project table with no influence on how the work was playing out - expected to give anything and everything the “user-friendly” rubber stamp. A waste of time.

So the idea came up to make us cost-recoverable, to ensure that the teams who brought us in really wanted us there.

Can you guess what happened? Deafening silence, crickets, tumbleweeds…

As soon as project managers had to start approving timesheets for us, filling in forms and yaddayadda - they stopped caring about the design tick-boxes for their project (and that didn’t cause them any adverse consequences from their project boards, so they were proven right).

The matter for a consultancy like the Australian Government Consulting (AGC) that may be a different kettle of fish, as I expect they deal with meatier, more structured programmes. But nevertheless, the psychology and bureaucracy behind how you get an internal resource onto your piece of work can make a massive different to its uptake, and thus, to its theoretical effectiveness.

Leading me to the second point: the UK simply re-prioritising budget away into other directions.

First and foremost, a political choice

At the risk of sounding cynical, but any government in any country is capable of simply re-shuffling funding for certain initiatives – FOR REASONS – nothing more, nor less. You only need to look at the manifold interpretations we’re seeing around budget day every year to see how a budget decision can be interpreted in a whole lot of ways by different players. And that’s fine, that’s democracy – but make no mistake, there is no such thing as one unequivocal truth around what motivated such a decision, imho. The best – and perhaps saddest – example is 18F, the USA’s in-house digital services consultancy that was one of the first heads-on-a-spike paraded by DOGE in their early days.

The point is that in a system where “success” is much more difficult to measure than through shareholder value, a decision such as the (dis)establishment of in-house consultants for public service has a lot more to do with political strategy, influence and conviction.

With that in mind, we should as:

What do we consider “success” here?

To my great delight, I found an early paper by Melbourne’s School of Government: “In-house consulting—a critical appraisal” (should be open-access). Marty Bortz eloquently characterises the ever-expanding reliance on consultants in Australia’s Public Service and points to the critical “hollowing-out” of public capability over time as turnover increases and the knowledge that the public sector develops just doesn’t stick (sounds familiar, no?). But he condeeds:

“We really are in unchartered territory when it comes to bringing consulting work in house”

Still, are there signs that such an in-house consultancy is efficient and effective?

Thing is, the way we fund, procure and account for government spent is way to complex to make a right-pocket, left-pocket calculation after a few years of piloting – and that is the same across Oz and NZ. So we’d face some difficulties of assessing 1:1 that a dollar spent on in-house consulting saves X dollars that would otherwise go external. There’s also a question of coulda, shoulda, woulda - how do we know an external gang would have been hired, if it were not for the internal resource, and vice versa?

Plus, on the matter of tax-savings, a small “pilot” unit may well be set up to fail. Bortz points to the consultancy’s relatively modest funding in proportion to the amount spent on external consultants, and calls this an “issue of scale”. With “over 30 staff” - how can they really show their impact in numbers, at scale, in two years?

While my monkey-brain also jumped to the question of cost and how much tax-payer money might be saved by using in-house talent - I’ve come to believe:

The question of whether there’s value in building public service consulting-expertise “in-house” in the classic fields of strategy, ways of working and funding cannot first- and foremost be an economical one – because the issues that the existance of such a resource would address are not solely monetary either. This concerns public expertise, control, ethos, stewardship and trusted advice.

As Marty writes:

“The underlying logic is that dependency and hollowing out can be countered by building the capabilities of the public service; by being smarter in the kinds of projects that are actually outsourced; and by providing a public service agency dedicated to evaluation (which is one of the main areas where consultants are used in Australia).”

By all means, we should also look at efficiency and effectiveness – but first and foremost, this is a policy decision.

In the face of long lists of concerns with the current extent to which we use external consultants - is there really an alternative to looking inwards?

And let’s check our expectations - such capability won’t get it right from day one. It will be faced with the same systemtic barriers that all public servants face when they try to make small changes in their working environment. It will need to wrestle with credibility, hiring the right staff, and negotiate its role in supporting a project as well as the people on it.

But in that, they are NO different - and certainly not worse - in their positioning than external consultants! Our over-emphasis on the annual external consultant bill may have blinkered us for the other systemic issues that the public service’s reliance on their service has. This is where it seems we could learn a thing or two from the APS, their inquiry and their efforts to address its findings.

No solution like an internal consulation-service comes out the box, ready to use, no issues. But establishing a new capability, giving it a fair shot at findings its feet, and evaluating its success in proportion to its scale, is a heck of a better approach than forever cutting- and increasing consultancy spent and waiting for something to magially change.

Bortz pus it quite dramatically in his closing thoughts:

“The expanding role that consultants have played may just suggest that government in its current form is no longer fit-for-purpose and that we need to reconsider the very foundations of some of our most enduring institutions.”

I’m not sure I’d go that far, but I agree that the role of consultantsin public service goes far beyond their billable hours. Let’s not under-estimate the symbolic and cultural impact that the establishment of an in-house consultancy for leaders in the public service might have: one of a public service that does not under-value its buying power, its thought-leadership in dealing with wicked problems, and its role in a functioning democracy – and one that stops constantly looking to private sector firms for advice on strategies, ways of working and financial concerns.