The conviction I hear about most when I tell someone that I study restructuring is that it’s just a way to get rid of “bad apples”. Managers just don't want to go down the legal path and put someone in their team on “performance management” (or “can't be bothered to” as many people phrase it). So they “realign” their team under some fig leaf explanation - because of course managers don't actually use the word “restructure”, EVER - and the person or people in question are either directly made redundant or go through a contestable process where they are found not to be the best candidate.

It's a compellingly simple and practical explanation, but a bit tricky to substantiate academically. In 2012 Norman and Gill wrote an excellent paper on the focus groups they ran with CEOs from public service organisations, human resources teams and PSA representatives, asking them about their views on restructuring. They found:

“Human Resource Managers thought that restructuring has become almost a ‘preferred and first choice method for tackling individual performance problems’, a way of avoiding potentially long drawn-out performance processes.”

CEOs we're not as direct, they spoke more to the political expectations and strategic necessities that lead to structural changes (I expect to write about that another time). When it came to personnel one said:

“You can't drive change as one person. (…) if you're going to change you have to start with a team that you believe can help you drive that change.”

So they highlighted more of the trust side - and honestly, who doesn't want to work in a team where you fully trust every single member?

In my PhD research I found an odd pattern that may substantiate the idea that “removing bad apples” really is one of the main reasons that restructures happened as often as they do. I counted all impacts on roles that restructures had between 2018 and 2021, and:

I found there were five different types of impacts that I could differentiate by what the main kind of role change was.

For example, in “Rearrange” restructures a majority receive a new reporting line, in “Finetunes”, most people are not affected and only a small number of roles in the team are changed. This table shows in which proportions are found these impact types:

The replacement of existing roles with new ones is by far the most common restructure effect with 38% of all restructures. The headcount of the team stays more or less the same as a considerable number of roles is made redundant and a similar number of new roles is created that the incumbents can apply for.

More often than not, the newly created roles have strikingly similar titles to the ones that are disestablished. No reasoning is given why roles are disestablished and replaced instead of being changed – in a number of cases even with the exact same role title.

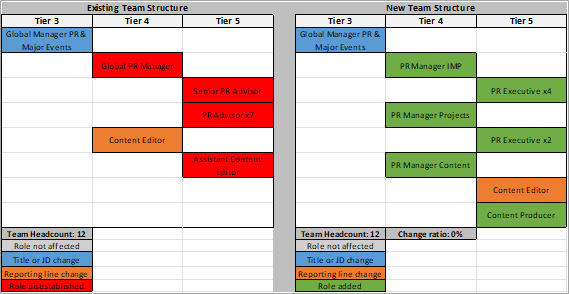

In this restructure from 2018 seven “PR Advisors” were made redundant and six new “PR Executive” roles were established and placed into an extended middle management structure:

This can mean that many of the same people continue to be employed under new titles (after going through a formal application process), or that staff leave if they are deemed not transferable to new roles.

One interpretation is that this action gives managers the opportunity to selectively re-employ people or let them go.

I don't believe that this is true for all restructures, honestly I have no idea how many this might be true for. It is odd, though... Replacements are so common, and remember that this is in a time of growth between 2018 and 2021. To my understanding, it is legally possible to change someone’s job description and title in a restructure. With many examples in my data showing very similar titles being disestablished and newly added - it's hard to explain this any other way.

Perhaps I'm missing something important here, I'm no expert in HR or employment law. But it could well be that this common belief that people like to share with me really has some legs.

Performance management sure can't be easy, for either party involved. An example I was once privy to was hugely destructive for manager and employee alike, so it's not bizarre to think that managers may choose the path of least resistance. And I do believe there's always more to that decision as well. Norman and Gill (2012) cite their participants saying that restructuring is a “rite of passage”, so there is a lot more to be gained for managers from being seen to run a restructure.

The authors also call restructuring “an addiction”,

- because it has to be said, the waves that these events make in the lives of employees are massive, and even if you understand what might incentivise managers to run them anyway, you sure don’t have to like it.