When you learn about public management in New Zealand, one dreaded term keeps popping up that you have to content with: “New Public Management” (NPM). It's a clunky label for the public sector reforms of the late 80s and 90s (with some spillover in the early 2000s), that you can broadly describe as the effort to make the public sector act more “business-like”. And New Zealand is often called its poster child.

Our reforms were, in common parlays, extra radial, theory-based and politicised. I could easily get bogged down in the details here, but let’s just name a few: we separated policy, regulatory and delivery functions, we centralised funding and purchasing, and we redefined the “accountability” criteria for public CEO’s and their relationships with ministers.

Overall, the term “neo-liberal” is never far from discussions on NPM, a whiff of Eau-de-Thatcher in the air.

It’s possible that New Zealand has a bit of an undeserved reputation as a “radical NPM adopter” here, but the reaction of my peers at conferences tells me that there certainly IS a reputation. And considering our current discourse about public service, it might do us good to zoom out. Fair warning, I’m no deep specialist in this and some of what I’ll write will be simplistic for the sake of the argument.

Because, IF our public sector has been made to be so “business-like”, then we should also see some of those neo-liberal practices at work, no?

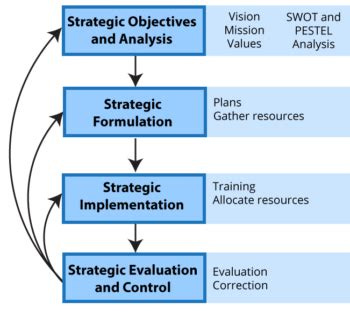

My pathway into this has been reading up on “Strategic Management”, strategic planning methods and the likes. It’s quite the field, very TED-talky. Any off-the-shelf airport book on management will have some sort of version of this (license-free) model:

The cycle always goes: vision, analysis, planning, implementation, monitoring -> back to the start. Right?

The one block in this cycle that I would argue is the weak (or perhaps missing) link in public service is the last one: evaluation & control. Aka monitoring.

Consistently across PRINCE2-style projects or agile-ish pieces of work I’ve been on, once the big push to get something out the door was done – poof! Funding is gone, the steering group members run for the hills, and – all to often – operations find themselves catching a hospital pass. To have someone to feel (or formally be) responsible to check in after a while and see if the vision was being fulfilled, the benefits were realised, was a rarity in my experience. No, such efforts seems to be reserved only for the most massive, multi-year, budget-busting initiatives.

And equally in my research on restructuring, I have reported before that only 11 out of well-over 400 restructures ran some kind of post-implementation assessment (it was 9 in my original post, I found 2 more!).

This isn’t a breaking-news revelations, but when we ask what the public service has (and should) learn from the private sector, we can’t sail past this issue.

Fundamentally, any private institution has a common motivator – cash. So there is a natural incentive to monitoring and evaluation - someone needs to tell me if I make more or less money! But in the public sector the incentives are not as clear cut; yes there is a fiscal responsibility, but the state also has to do things that are not a popular product you would choose to buy, like regulation. Measuring success, money well spent, dividends, all that is a whole lot more difficult – so we might just… not?

Someone I spoke with recently put it this way: The state is a monopoly, and acts accordingly.

There's a level of transparency for private sector companies of a certain statue that is legally required by the state. The way it was described to me by a board member of a large international company was, paraphrased:

If I want to do a restructure, I need to publish my plans and my motivations both internally and externally. And if there is a Business Analyst internally that does some numbers and makes a good case of why parts of my idea don’t work, then management looks very poor if they don’t listen to that feedback. So they need to take it serious.

I can’t attest to such a situation myself, and there are plenty of stories of companies obfuscating transparency, but I broadly get their point that there are some – regulated – mechanisms for transparency, monitoring and accountability that I struggle to see translated in the public sector.

This is such a difficult topic, because it so easily falls into pub-fuelled bravado and generic notions of “the public sector sucks”. I decides to reflect on it here, nevertheless, because I think there’s something here to consider that may not get enough attention.

So why so we seemingly skip a building block of management “best practice”?

One crucial factor that often gets overlooked in this discourse is the role of political leaders in this. And this takes us to the point where New Zealand may actually be quite unique, and that might explain its “poster child” reputation: With 3-year election cycles and a centralised, single-chamber government, the speed at which political decisions can happen is break-neck compared to similar states.

I know it doesn’t always feel it when you’ve never lived elsewhere to compare. In my native Germany, there are two federal chambers to be cleared, plus a layer of EU policy in some cases and discussions at the individual state-level in others. Policy changes take YEARS and no one is surprised when a new government is well into their second year before any election goals break the surface (in the rare case that they do).

Regardless of the party in charge – New Zealand’s elected members can unleash a massive load of policy-changes onto the public service, at what feels like the snap of a finger sometimes. And this may be unfair, but I have the impression that especially those career-politicians who never worked in public sector themselves have little to no appreciation for the cascade of waves that each new order sets loose, and the amount of administrative effort and coordination required to plan, realise and embed a new order.

In short – New Zealand may well be unique in the world of Westminster-ish systems for its break-neck pace of continuous change from the top.

Seen from this angle, the lack of monitoring and managerial accountability – that I am equally frustrated by – may well be a survival-mechanism, a form of adaption.

A system that constantly has a new order, idea or strategic change in the pipeline incentivises action over reflection. And when the orders are not tied to clear markers, metrics and indicators, it’s more important to be seen to do something HERE and NOW, than to do the hard yards of overseeing a gradual and measured evolution of complex systems.

And because we still value transparency, we deal with it in the only way we can: by producing a lot of documentation and paperwork. SO many excel sheets and power points, artifacts of busy-work. So when we OIA things, we can play public service archaeologist and ask ourselves: what the hell where they thinking when they did this? Only, after the fact.

Which may well be why the Dom Post test is such a central part to our public sector understanding of risk: can we look bad when someone finds out about this after the fact?

So no, I don’t to see how anyone could call New Zealand a real neo-liberal poster child of New Public Management. Recent discussions around privatised health care certainly tick a few boxes there, but in the sense of our institutional ecosystem – what makes New Zealand unique (and dare I say, odd) in the world of public management may well stem from other systemic settings. And on our political practices, to say the least.

On that note, I highly recommend you read this post by Natalia on public sector accountability, as she is much more versed in politics than yours truly. And this topic, as so many, has so many more facets than one post can cover.

Oh wow! Thanks for the very generous shoutout my dear! Look at us writing and sharing our amazing knowledge together on here ? 💗