In your working life, there are moments when you form a new understanding of the way that the corporate world is made that feels like a real step up. Something you begin to see everywhere, where puzzle pieces fall into place and suddenly fit. The role of workarounds was one of those things for me.

It happened when I worked with a team of - let’s say broadly - engineers who were handling very complex applications from the public. They themselves had long been frustrated with how long it took to run an application, and they were hoping that a new IT system would make things easier and faster (sound familiar?). In this case, my team and I had the rare opportunity to do research before a piece of software was bought (a singular event in my career).

Interviews with team members proved confusing, they all seem to explain their work differently. So we got them all into a large room where we had covered the walls in wire diagrams of how they had described their work process. We gave them pens and asked them to correct the diagrams. This was our way of getting the facts straight in one go. We didn't expect to see massive discussions breaking out between the team members. They gathered around a point in the process and argued back and forth what was supposed to happen there, what policy applied, or what the ‘best practice’ here was. After a few rounds, I remember one person exclaiming:

“Oh my god, it's like we don't even work on the same thing!”

For engineers this is particularly frustrating because policy, process, and practice are supposed to be clear-cut, repeatable and reliable. What we really had here was a team that had been under so much pressure, so under-resourced, and missing decent tools for so long, that they had developed a massive, twisted system of workarounds (sound familiar, again?).

So what do I mean by workarounds?

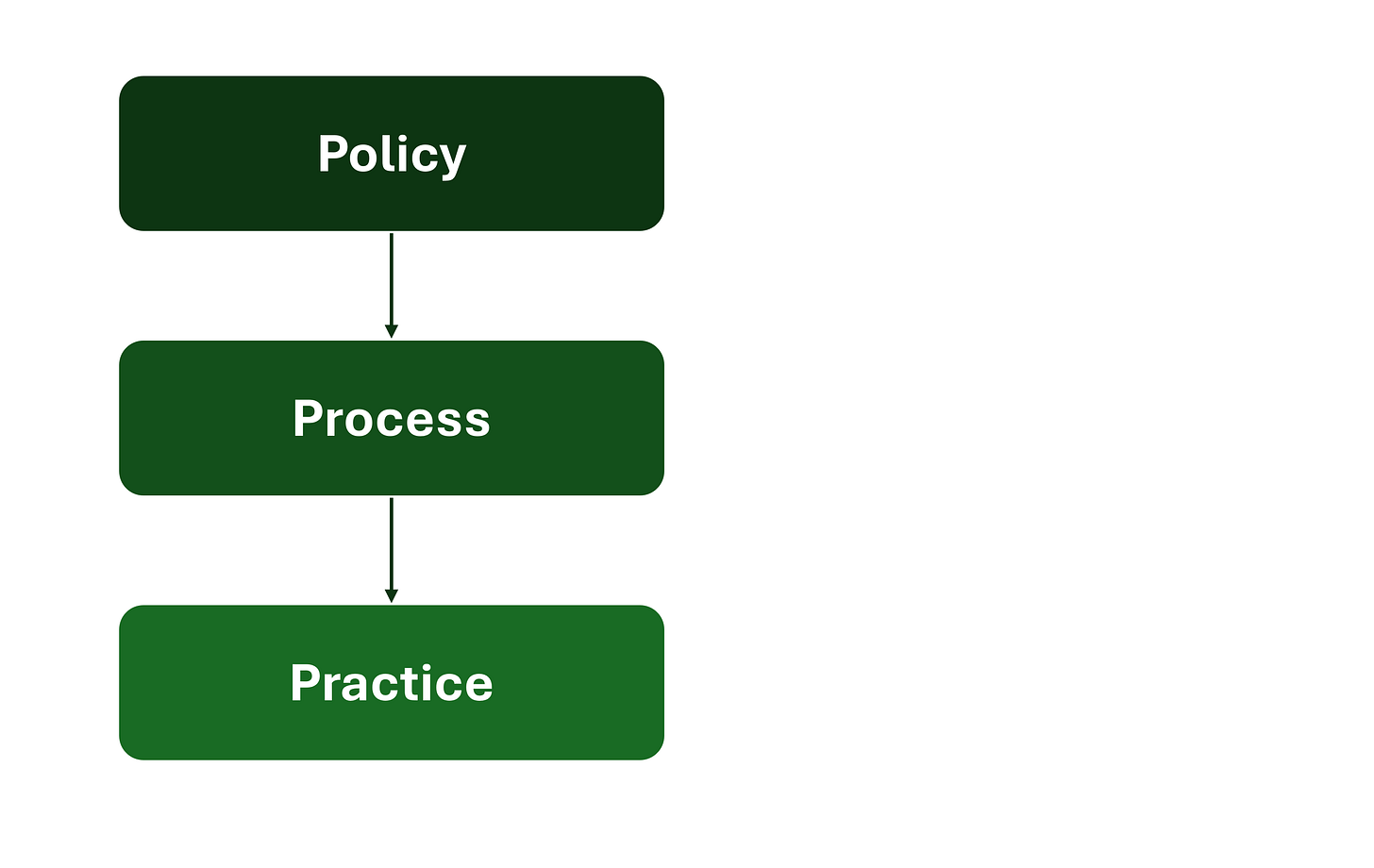

We start with a lovely diagram of how work is supposed to be organised, particularly in large institutions: a policy sets out what is supposed to happen, the process says ‘how’ that's supposed to happen, and the practice does the ‘small’ stuff, like who, when, with what. Neat!

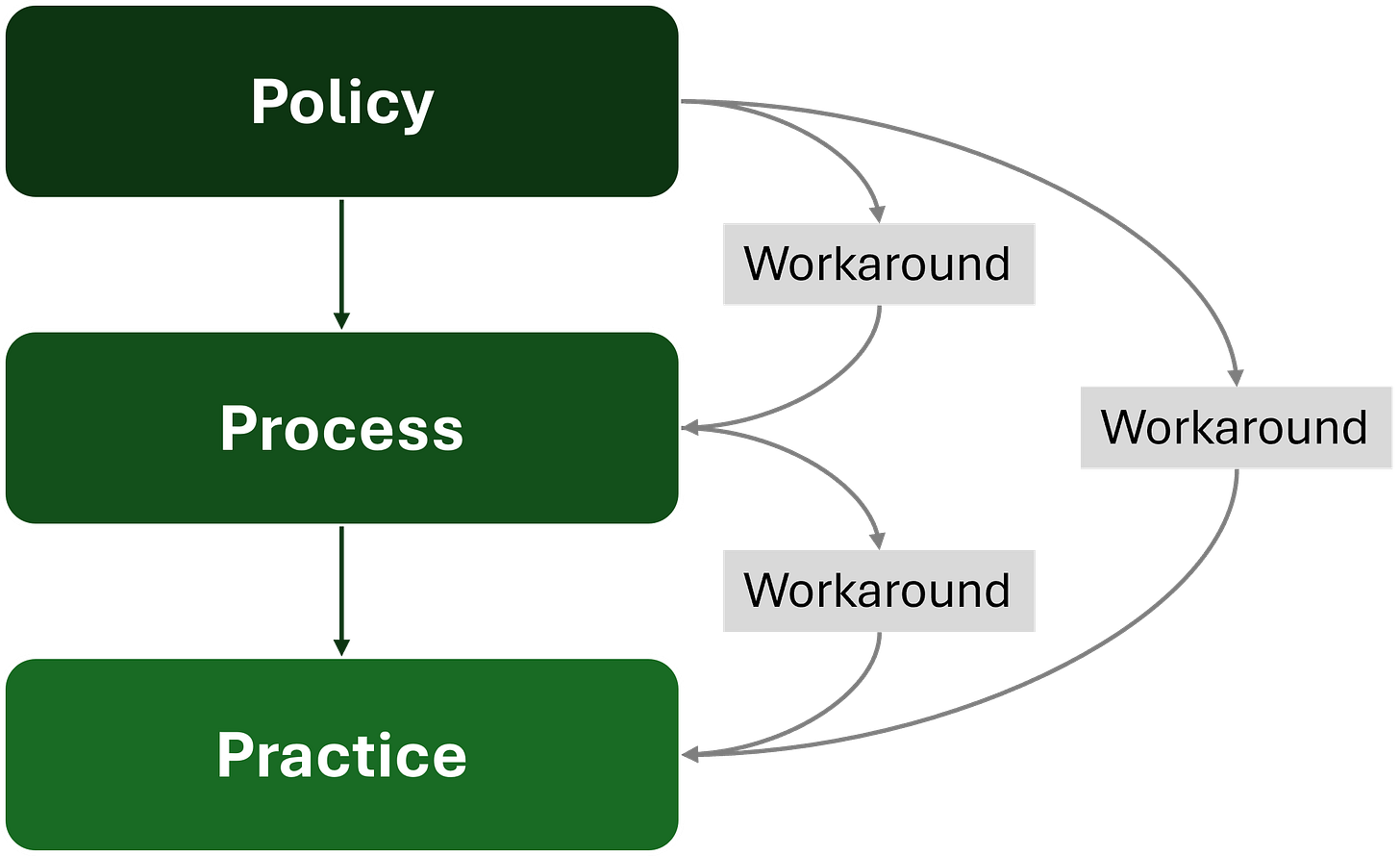

But then your team doesn't have enough budget to hire as many people as needed to run the process at pace, you have no formal training so newbies get ‘buddy-trained’, and your specialist software is based on an outdated code, held together by blu-tack and rubber bands, and never worked as intended in the first place. So at each point between your process, policy, and practice, you and your smart, stressed teammates come up with a way - any way - to get things done. And there’s your workarounds.

As time goes on, the buddy-trained people train new buddies, people bring in their personal foibles, things get lost in translation, and the policy is updated but your process and practice is not - now the workarounds develop their own workarounds.

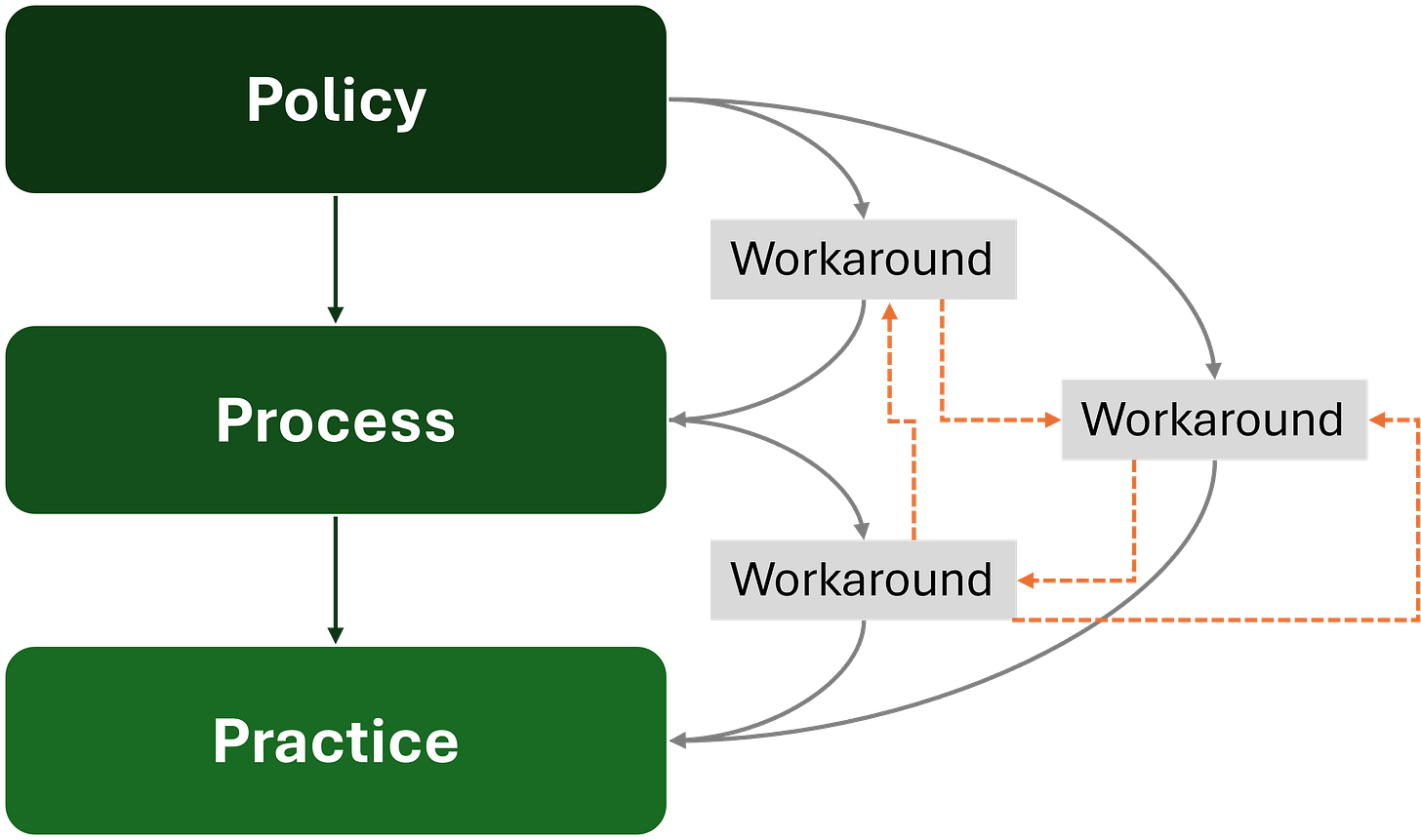

This will be blatantly obvious to anyone who has worked in a corporate environment, private or public. This UK-based paper from Goff et al (2021) raises that workarounds are not negative per se - they are often necessary and can be productive.

There is no ideal world in which everything I mentioned above is somehow in balance – the right team size, workload, effortless IT, all resources in check. So there will always be some need to make things work with less (now perhaps more than ever in New Zealand’s public service, yikes!).

But here's the snag: managers - even the ones who are quite close to their teams’ practice - often don't know the workarounds their team members have, or at least not all of them. So when our way of improving policy, process and practice is so focused on the opinions and knowledge of managers and their consultants as it is, the information on workarounds is often not represented. Even though they point us to the critical points where change is needed, and to the areas where things don’t work out as planned (and there are plenty of those).

Good design comes from limitations

And few things can tell you more about the limitations that a team faces then the workarounds they had to develop. That's why I believe that workarounds are one of the most criminally underestimated and undervalued part of our working ecosystem. Not knowing them, or not designing with them in mind, is a major reason why so much organisational change doesn't pan out in practice. It’s like trying to solve a puzzle with the corner bits missing.